A Curious Man

Robert Anthony Fife, 1933-2024

I never saw my mother eat.

Robert Anthony Fife, my father-in-law, who died in February a month shy of his 91st birthday, said that this would be the first sentence of his autobiography if he wrote one. I don’t know if he ever tried to put something down on paper, but for a time the notion was on his mind. He had taken inspiration from reading Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt’s memoir of growing up desperately poor in a dysfunctional Irish-American household. Robert thought, rightly, that there was something compelling in the story of his own hard-luck childhood and how he and his sisters and brother had—and had not—left it behind.

By the time Robert was conscious of the world, he and his siblings were living in a Catholic children’s home in Cleveland, Ohio, and their mother Delia, an Irish immigrant, had been institutionalized for what by all accounts was severe postpartum depression. She’d given birth in her thirties to four babies—Janet, Robert, James, and Julie—in the span of five years, one after the other. Her husband, also named Robert, was an alcoholic who was incapable of caring for the children, so they were taken in by the church. As an older child, my father-in-law paid some visits to Delia, but as he said, they never ate food together, which bothered him as he got older. “Isn’t that curious?” he would say; it was something he said often, in both wonder and perplexity. Bonding with family over meals is such a fundamental, everyday experience that most of us hardly think about it. Robert thought about it. His mother remained a cipher to him throughout his life, and in his mind the mystery of her was all bound up in the fact that he had never seen her eat.

Given his nature, he must have felt the lack of connection with his mother keenly. Getting to know and understand other people was the great work of Robert’s life, and had been from childhood. He would set people at ease with his humor and stories about other people he knew or things he’d read, establishing a rapport, and all the time he would be watching and listening and learning, absorbing who they were. At his best, he seemed to have a bottomless capacity for finding other individuals interesting—their habits, their motivations, their memories, and their insights—and he took the time to pay attention to them.

One result of this attentiveness was his truly phenomenal memory for the full names of people he’d met over the years, including his fellow children at the home, most of whom he hadn’t seen in eight decades. More often than not, he had an anecdote or two and several biographical details to go along with the name. Until the last few years of his life, he hardly even had to work at it; the names and stories came to him unbidden. As with many people who have unusual gifts, he had no real sense of how unusual his gifts were—not just his feats of memory, but his ability to connect to others. When he talked about someone he’d known at the age of eight, he didn’t just remember the subject of a funny story, but rather a whole person who was real to him.

It’s as if the humanness in him (that is, the qualities that make us specifically human) was turned up to a higher level. Before people invented writing, men and women like Robert would have been the historians, the lore-keepers. They would have been the centers of vast webs of social connections. They would have been the glue that held communities together. They would have been the genealogists who remembered all the lineages, all the names.

Names were important to Robert. I am calling him Robert here although it doesn’t come naturally to me to do so; for nearly thirty years, I called him Bob, as other people did. But in his last year, he expressed a wish for people to refer to him by his full given name, and in retrospect it’s a little surprising he didn’t make a point of it earlier. He habitually used full first names when he addressed others. His wife Kathy was Kathleen, my wife Jen was Jennifer, Jen’s brothers Andy and Dan were Andrew and Daniel, and I was always Stephen. (Only Jen’s eldest brother, whose name is also Robert, retained the nickname of Bob.)

This particularity about names could seem oddly formal coming from a man who had such a prodigious talent for putting others at ease and making them feel befriended. But I think the two qualities were closely related in him. Robert’s approach to other people was rooted in a baseline assumption of mutual respect, and one way he could signify respect was to call a person by their full name.

I have worried, in the months since he died, that he might have felt a tiny bit slighted by me every time I called him Bob when he was calling me Stephen. But if he did, he never let on. The rules he lived by were only for himself.

***

My notion of Robert’s life in the children’s home is that it was predictably unpleasant in a Dickensian way. I don’t know if that’s a fully accurate picture or just a reflection of my assumptions about children’s homes. A story he liked to tell was about the time he stuffed the creamed onions from his dinner plate into his pocket when the adults weren’t watching so he could be excused from the table. “I feel sorry for the person who had to clean those trousers,” he said with characteristic empathy. In my mind, the detail of the creamed onions—creamed onions—conjures entire tableaux of misery.

Robert’s Dickensian childhood evolved into a Kingsolverian adolescence. As adolescent boys do, he became unruly and uncontainable, and he was sent from the home to a foster family’s farm outside Cleveland, where he was put to work. He remembered his time there as a mix of wretchedness—he was forced to sleep in the barn “with the other animals” after wetting the bed one too many times—and relative freedom. The bed-wetting may have been a trauma response to sexual abuse he experienced during those years. Sometimes volunteer members of the community would take the “orphans” to the movies on the weekend, and one of those volunteers took liberties with Robert and presumably other children. This was an episode that he kept buried for most of his life. Yet in another demonstration of his remarkable capacity for empathy, he was ready to talk about what had happened, and about the feelings of shame and anger he’d carried with him, when someone close to him shared their own story of abuse.

Robert’s older sister Janet stayed in touch with him throughout his time on the farm and kept him connected not only with his younger brother and sister but also their parents. She would have been the one to arrange visits with Delia, and when Robert finally ran away from the farm, she was able to direct him to their father, who took him in. It does not seem to have been a happy reunion. The elder Robert’s drinking was out of control, and the younger Robert wound up having to take care of him.

My father-in-law’s prospects at this point in his life did not have a promising trajectory. So he did what a fair number of young men still did at the time and lied about his age so he could join the Marines. Boot camp was the first place he’d ever been where he could eat until he was no longer hungry. While he was there, his father died. Robert Sr. had a heart attack, and upon being discharged from the hospital, he’d gone straight to the pub, gotten drunk, and had another heart attack that finished him off.

Free to begin a new life, Robert flourished in the Marines. He was sent to Korea at a time when there was still active fighting and became a tank commander. His stories about his time there shied away from his experience of combat and focused more on the hard work, the noise, the smells (hot engine oil and body odor in the tank, fields fertilized with human feces), his comrades and rivals, and the cheeky attitude he took with his commanding officers.

He surprised some of us with the decision he made to have his ashes interred in the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery with military honors. As the end of his life drew near, the outsized place in his psyche of his time in the Marines became evident. He’d always been an inveterate re-watcher of movies, usually ones that featured crises of honor and dramatic conflicts between alpha males: The Godfather, A Few Good Men, Heat, The Shawshank Redemption. The last few times I saw him, he’d become absorbed in older black-and-white war movies, especially WWII prison escape films like Stalag 17 and Break to Freedom. I wondered if he was feeling trapped in a body that no longer did what he wanted it to do and was dreaming of his own break to freedom.

***

Robert’s time in the Marines drew a stark before-and-after dividing line in his life. He left a traumatized, angry, and aimless boy and came back a confident, capable, and motivated young man ready to get a job and get on with things. He was also a rambunctious ladies’ man. (This was when his life turned Updikean.) His sister Janet, playing matchmaker, introduced him to Ruth Schlachter, a serious young woman she thought would keep him on the straight and narrow. They married in 1956—he was 23, she was 21—and for $12,000 bought the house in Parma, Ohio that Ruth would live in for the rest of her life. Robert later said he knew on their honeymoon that he had made a mistake, that he and Ruth were not compatible. I got to know each of them when Jen and I started dating in the mid-1990s, two decades after their divorce, and it always seemed fairly incredible to me that they had ever been married. Robert was a boundlessly curious man, while Ruth was one of the most incurious people I’ve ever met. He was always restless for new and different things; she was committed to routine and fearful of change. He tried out a number of careers, his favorite being teaching, and went to college at night on the GI Bill, trying to expand his horizons; she kept her horizons as close and narrow as she could. On the one hand, Robert craved a mother, and Ruth was willing to mother him. On the other hand, and this is speculation of course, Robert wouldn’t have necessarily wanted to have a mother in the bedroom.

Things might not have gone the way they did, and their differing natures may not have driven them so far apart, if they had been able to build the busy family both of them wanted. Their first baby, Bob, survived and thrived and was beloved by them both. But after Bob, there were two who died within a day or two of being born along with several miscarriages. They didn’t know that Ruth was already suffering from the effects of multiple sclerosis. Robert, meanwhile, spent plenty of time outside the home, working, and going to school, and socializing, and having affairs.

By the late 1960s, grieving the children they’d lost and hoping to shore up their marriage, Robert and Ruth had put in a request to adopt a baby through Catholic Services, and in 1969, at six weeks old, my wife Jen came home with them. For Jen, being Robert’s daughter would become one of the most rewarding aspects and strongest foundational pillars of her life. But in the short term, her arrival could not keep Robert and Ruth together. Robert stayed disengaged, and within a couple of years, he started an affair with the woman who would become his second wife, Kathleen Wenstrup, who gave him an ultimatum that if he wanted to keep her he would have to leave his wife. Kathleen was serious in a different way from Ruth, more intellectual and worldly-wise, and she shared his sense of adventure, his good humor, his curiosity about the world, and his enjoyment of a good time. In 1974, he moved out of the house in Parma and asked Ruth for a divorce. In Jen’s four-year-old mind, the drama of the Watergate hearings on television became intertwined with the drama in her household, and she blamed Richard Nixon for the dissolution of her parents’ marriage.

***

Early in his adulthood, Robert left his impoverished childhood behind and moved squarely into the middle class. It’s the kind of classic American Dream story that some people are thinking about when they say Make America Great Again, a story that has become out of reach for more and more working-class people in the past four decades. He was able to do this because there were good paying jobs for people without degrees, because there was the GI Bill, and because people took a chance on him. Even before he’d completed his hard-earned college degree, Robert was able to make a living that supported a family and paid a mortgage. He loved his job as the principal of a vocational school, but sales was where the money was for someone with his talents. He wasn’t the type to make plans; his career unfolded organically as he followed his interests and stayed alert for the opportunities that came his way. For a couple of years, he worked the Midwest territory for Prentice-Hall, visiting college professors to bring them the newest editions of standard textbooks. It was the one job he later regretted having left for a better-paying position. The educational world stimulated him, and while I don’t think he ever would have become an academic—he loved books but preferred people—he would have made a great teacher (and student) of history.

By the time I met Robert, in 1994, he and Kathleen had been married nearly as long as he and Ruth had been, and they had two teenage sons, Andrew and Daniel. Jen lived with the four of them in a comfortable house in the western Chicago suburb of Naperville, Illinois, a classic middle class Midwest town that was just starting to become the upscale bougie place it is today. Everything I’ve said up to now about Robert’s character was evident to me very early on in our acquaintance. He welcomed me into the family immediately (as did Daniel, who inherited his father’s social skills and sharp perceptions about other people). I felt seen by him. His curiosity about me was genuine, his intelligence was palpable, his stories were hilarious. There was no awkwardness, no friction. Until, very suddenly one evening, there was.

I’m not sure why I wound up running a load of laundry in their washing machine—maybe we’d gone swimming at Centennial Park and I was trying to help out by washing the towels—but I didn’t know to check the utility tub into which the water drained. There was something blocking the drain, and water wound up going all over the basement floor. Robert flew into a purple-faced rage at the sight of it and cursed at me when I tried to help clean up the mess. I fled upstairs to Jen’s bedroom for the rest of the evening, certain I would be unwelcome in Robert Fife’s house from then on. The next morning, I was in the bathroom, naked and just out of the shower, when Robert knocked on the door and asked to talk to me. While I stood there dripping with a towel around my waist, he shamefacedly apologized. “I got out of line,” he said. “It was just a little water, for Pete’s sake. Don’t know why I fly off the handle like that. I hope you won’t think worse of me, Stephen.” I said I wouldn’t, it was all good, and he nodded, and went off to work. I felt like I’d been given a reprieve. It wasn’t until much later that I realized how difficult it must have been for him to do that. He could have just gone to work, pretended nothing had happened, swept it under the rug. But that wasn’t how Robert Fife went through life, at least not by the time I met him at age sixty-one.

That was my first exposure to one of Robert’s rages. It wasn’t the last, although the heat was never again directed at me. Andy and Dan in particular could set him off, but it was Kathy who bore the brunt of it. It could be hard to reconcile the warm, friendly, gregarious man he was most of the time with the vein-popping tyrant he became in his worst moments; all that innate warmth seemed to get bottled up and explode. But as I’ve been learning in my own therapy, all of us have different parts that come to the fore at different times. Our selves that have experienced hurt or fear or shame or trauma can linger under the surface, emerging when they sense they are needed to protect us in some way. Robert had gone through more than his fair share of hurt, fear, shame, and trauma in his youth, and much of it had lain there unexamined for decades. On top of that, the rheumatoid arthritis he was diagnosed with in the second half of his life and the bad knees he’d gotten from crouching in a tank caused him persistent pain that wore down his reserves. It’s no wonder that sometimes a scared, angry, enraged, defiant and petulant boy peeked out from behind the curtain of his grown-up self.

The heart attack he suffered two years after I’d met him marked another before-and-after divide in his life. His father had died in his early sixties of a heart attack; so would his younger brother Jim. Robert survived, and he took seriously his doctor’s injunction to reduce his stress and change his lifestyle. He took anger management classes and started to work through some of the root causes of his tirades. I could see him doing the work. There would be moments when Kathy or one of the boys would say something, and I would see a flicker of annoyance or a scowl of anger flash across his face, and then he would pause and collect himself and break out into a grin, laughing inwardly at himself. Humor could dissipate the storm clouds and bring out the sunshine in the blink of an eye.

***

There is much, much more I could say about Robert Fife; truly, his novelistic life could fill a book. But this essay is getting long, and it is New Year’s Eve, and I want to get this out into the world before the year is over, so I will just say a couple more things.

There are people alive now who would in all likelihood have died had it not been for Robert’s kindness, compassion, and dedication to them. There are many more people like me whose lives would have been far poorer without the benefit of his friendship, humor, and curiosity. And there are untold numbers of people who never knew him personally but whose days were made a little better by a passing smile or joke or some small kind comment from him.

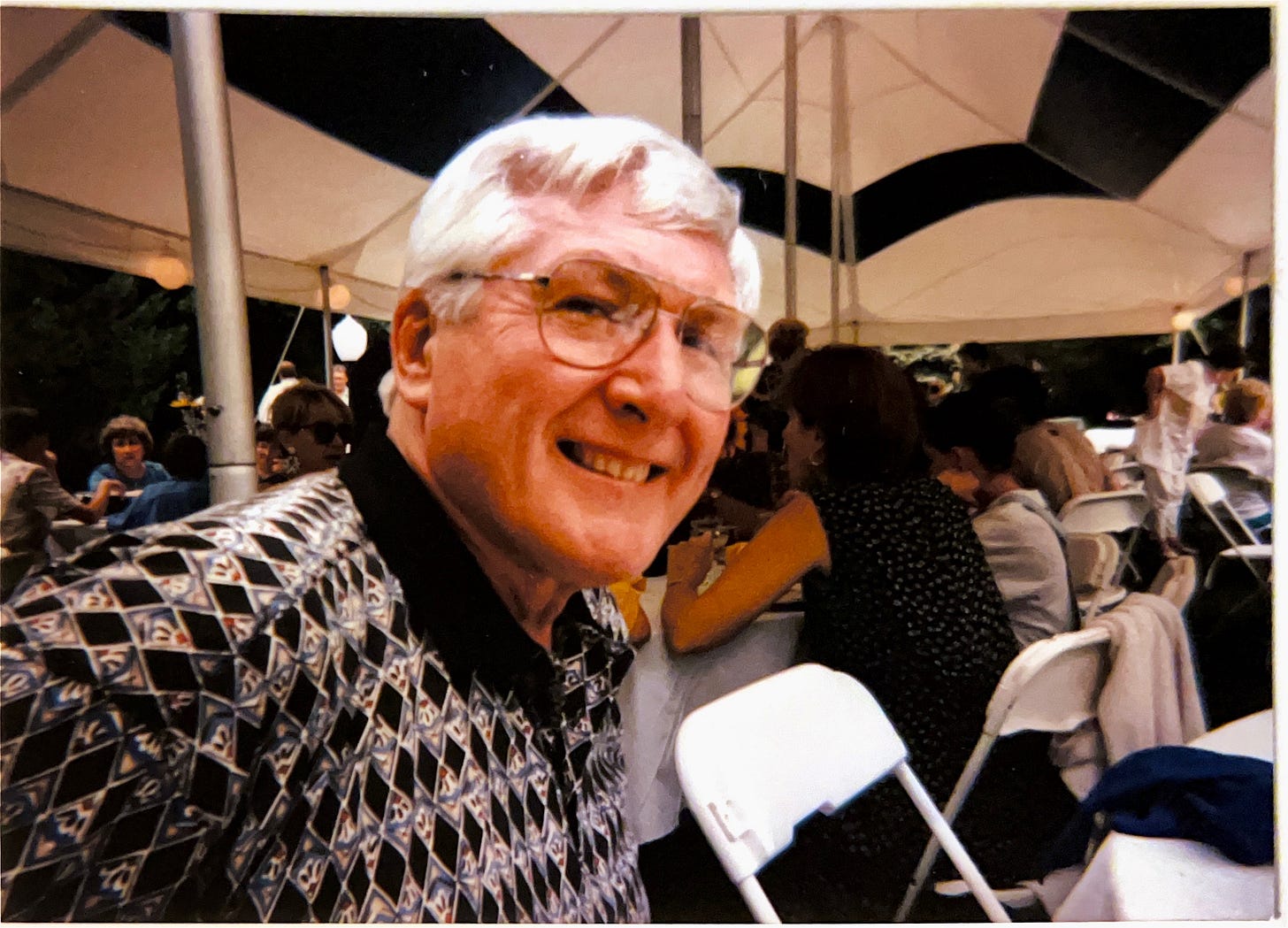

At the reception following his memorial service, there was a screen showing a loop of photos of Robert that spanned the time from his days in the Marines in the early 1950s to his ninetieth birthday in 2023. I stood and watched it for a while, marinating in my own memories of him, and then I went for a walk around the room, among the tables thronged with people, many of whom had known him and loved him all their lives. There was no one left who had known him all of his life; he was the last survivor of the four siblings, and if there was anyone from the children’s home still alive somewhere, it is unlikely they would have remembered Robert as well as he would have remembered them.

It was a good party, and a great group of people. But as I went from one table to another, I was struck by the sense that something was off. The room seemed muted, even though people were talking animatedly with each other, maybe catching up after not having seen each other for a while, or maybe telling funny stories of the things Robert had said and done, all of them eating and drinking and connecting. All of it was good, but something was missing.

Of course, it was someone that was missing. A loud voice and a big laugh from the life of the party, the soul of kindness, the man who had brought all those great people together, the center of gravity who had a gift for making a person feel they had a special place in his orbit.

The party went on, and so did life. But the center was gone, and it wouldn’t be the same without him.